Ballet has a long, rich history that stretches through centuries and across several different countries. Just as the contemporary ballet works we see today are very different from classical ballet pieces, the whole of ballet today is a far cry from what it looked like in the beginning.

Phase One: Origins of Ballet

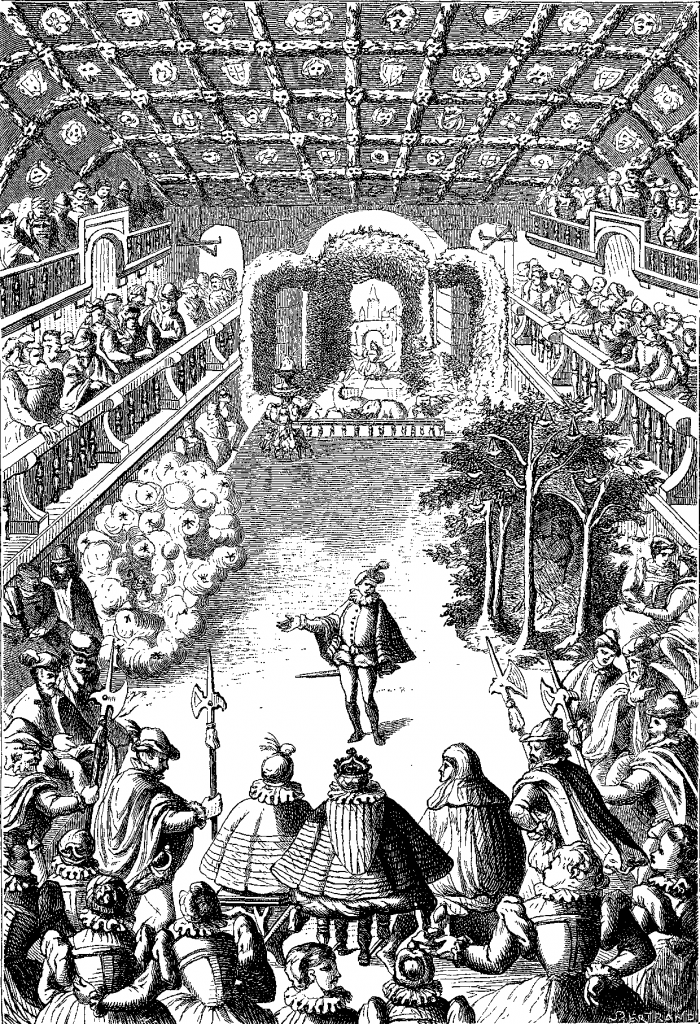

Ballet first appeared as a form of court dance in the Italian Renaissance. Court dancing consisted of nobles wearing many layers of heavy brocade dresses and tunics with headdresses, jewelry, and masks. All this formal clothing was very restrictive, so ballet in court dancing developed with small hops, gentle turns, and graceful glides. Ballet at this time was more participatory than what we see today—some nobles would perform in the beginning, and the audience would join in the dancing at the end.

An engraving of a scene in Ballet Comique de la Reine. Note the heavy, restricting costuming. Via Wikimedia commons.

In the early and mid-1500s, Catherine de’ Medici brought ballet to the French courts. She was an Italian aristocrat from the powerful Medici family in Florence who had married King Henry II of France. The Medici family were great patrons of the arts who funded dozens of famous artists, so it’s no surprise that Catherine de’ Medici wished to fund an art form in her new country. She introduced ballet to the French nobility, where it quickly caught on and became a popular court dance.

In 1581, Catherine de’ Medici put on an elaborate ballet performance for the wedding of two French nobles. Called Ballet Comique de la Reine, or The Queen’s Comic Ballet, it was the first recognized ballet performance due to the combination of theatrics, music, and choreography. Catherine de’ Medici’s triumphant first authentic performance and her funding of ballet in France set it on the course of development to what we know today.

Phase Two: Standardization of Ballet in France

Louis XIV, one of the most famous kings in European history, was the next French royal to advance ballet’s course. An avid dancer, Louis XIV made ballet hugely popular and performed many roles himself. Up to this point, ballet was still a court dance that had not been officially standardized or codified with terminology or positions.

King Louis XIV as the sun god Apollo in Ballet Royal de la Nuit (Royal Ballet of the Night), 1653. Via Wikimedia Commons.

However, Louis XIV wanted to elevate ballet to an art form that required professional training as opposed to just something to be picked up on and done for fun. His desires were politically motivated—he established the first strict rules of technique in ballet and turned it into a crucial element for court life that only the highly educated nobles could perform. And because he often gave himself the leading roles, he was held in higher esteem than any other noble. Through his desire to hold more power even in the world of dancing, he transformed ballet for the first time into a dance form that was regulated with rules and protocols.

When he grew too old for dancing, Louis XIV founded the Académie Royale de Musique (Royal Academy of Music) from which eventually developed the Paris Opera Ballet. Louis then hired professional dancers from his academy to take his place in ballet performances. Toward the end of the king’s life, Pierre Beauchamp—a dancer, composer, and choreographer—developed and standardized the five positions of the feet and arms. He also helped create names for the steps in ballet, which is why nearly all steps ballet dancers learn today are in French. This formalization of ballet into a codified system was revolutionary in the establishment of ballet as a formal discipline.

From Louis’s founding of the Académie Royale de Musique until the 1750s, ballet was only performed along with opera to give the audience a respite from the emotional intensity of the opera’s story. But in 1760, Jean-George Noverre published Les Lettres sur la danse et sur les ballets, which explained his ideas that ballet should be a standalone art form containing expressive, emotive movements and drama. Noverre’s work resulted in him being known today as the originator of the ballet d’action, or ballet that involves a narrative rather than just storyless dancing. His concept of the ballet d’action caught on quickly in France, and ballet performances then evolved into the classical ballet narrative performances we see today.

Phase Three: Development of Classical Ballet

Moving into the 1800s, ballet was heavily affected by Romanticism. This was a European movement concerned with the mysterious and supernatural. It manifested in ballet through the creation of Romantic ballets like La Sylphide and Giselle. Romanticism in ballet also meant women were viewed as delicate and ethereal, so it was the ideal environment for the development of pointe shoes.

Carlotte Grisi as Giselle, 1841. Via Wikimedia Commons.

For the first time, female ballet dancers were able to balance and dance on the tips of their toes, which made them look lighter than air—perfect for the portrayal of the ghostly spirits in Giselle and La Sylphide. Costumes also changed from courtly clothing to lighter, bell-shaped skirts that went to the dancer’s mid-calf to show her footwork en pointe.

As the Romantic period came to an end, classical ballet came to fruition in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Choreographers, instructors, and dancers began to move their focus upward from the feet into the legs, torso, and arms. Higher extensions, difficult turns and leaps, and full turnout became the standard in ballet. The stiff saucer-shaped tutu that comes to mind today was developed in this time to show off the dancers’ incredible technique and athleticism. It was during this time that ballets like The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake were created. The highly demanding technique that evolved during this period is still taught in classical ballet schools across the world today.

Phase Four: Development of Contemporary Ballet

In the early part of the 20th century, while classical ballet pieces were being written, some Russian instructors started incorporating modern dance techniques into classical ballet. In 1913, the choreographer Sergei Diaghilev worked with the composer Igor Stravinsky to stage The Rite of Spring, a ballet far ahead of its time. Its dissonant music, avant-garde costuming, and decidedly uncomfortable storyline sent shockwaves through the Russian population.

George Balanchine, a Russian-turned-American dancer and choreographer, further expanded the notion of contemporary ballet. His daring new methods earned him the titles of father of American ballet, creator of the Balanchine method, and founder of the New York City Ballet.

A performance of contemporary ballet. Via Les Grands Ballets Canadiens.

Balanchine staged ballets that had no plot, and his choreography broke many of the established rules of classical ballet. For example, he sometimes included turned-in legs and flexed feet in his choreography, his costuming was simplified into leotards and t-shirts, and his method trained dancers to have an open arabesque very different from the arabesque seen in classical ballet.

Today, the innovations of Balanchine and many other contemporary ballet pioneers like Twyla Tharp and Robert Joffrey are celebrated, taught, and performed by classical and contemporary ballet companies alike. Although the court dancing form of ballet is a thing of the past, the Romantic, classical, and contemporary ballets we see today are all descended from the steps of those Italian and French nobles from centuries ago.