Pointe shoes: to the audience, they’re those beautiful satin shoes that allow dancers to balance, jump, and turn right on the tips of their toes. To the seasoned dancers, they’re instruments of equal parts beauty and pain. To the youngest dancers, they’re a mysterious rite of passage that ballet dancers receive when they’re strong enough and old enough. Pointe shoes, like the larger ballet world, have a rich and dynamic history. They have an incredibly complicated production and breaking-in process, and they’re a bit like snowflakes: no two pairs of pointe shoes are exactly the same.

History

Ballet began in a much different form than we see today—it was a type of court dance in Renaissance Italy. In the 1500s, it was brought to France, where the language and basic movements of ballet were developed. (For a more complete history, check out our post on the history of ballet.) It was still a court dance, though, so the dancers wore heeled shoes all the way up through the 1700s and beyond. In the 1730s, Marie Camargo of the Paris Opéra Ballet removed the heels of her shoes to make them flat, which allowed her to perform larger leaps and faster movements than her fellow dancers. This was the beginning of the modern ballet shoe—both flat canvas shoes and pointe shoes.

Marie Taglioni in La Sylphide, via Wikmedia Commons.

From there, pointe shoes developed quickly. In the 1790s, Charles Diderot invented a wire rigging to float dancers onto their toes for an instant before lifting them into the air. Then in the 1830s, Marie Taglioni performed La Sylphide entirely en pointe, though her shoes were only heavily darned and tightly fitted flat shoes. This was during the Romantic period when stories about fairies, ghosts, and other supernatural beings were all the rage. Because of this, Taglioni’s technique quickly caught on with other dancers wishing to appear weightless and ethereal. Later on in the 19th century, Italian shoemakers began making stiffer pointe shoes by reinforcing flat shoes with newspaper, flour paste, and pasteboard.

Finally, in the early 20th century, prima ballerina Anna Pavlova reinforced her shoes with leather soles and a hardened box to support her high arches and tapered toes. Her method proved successful, and she commissioned a shoemaker, Salvatore Capezio, to outfit the entire Imperial Ballet company with her modified pointe shoes. This marked the first brand of pointe shoes, and the Capezio brand is still a large pointe shoe producer to this day.

Pointe shoes evolved from there to give dancers a longer vamp and wider box & platform, offering dancers more support and stability. Today, we see pointe shoes sold in a variety of shades to match all dancers’ skin tones, and some brands like Gaynor Minden make their shoes with materials like plastic and rubber instead of the layers of glue and paper that most other companies use.

Anatomy & Creation of Pointe Shoes

Pointe shoes are very different from street shoes and even canvas shoes in that the way they fit on the foot and the intense dancing done in them requires them to be fitted perfectly to each dancer’s individual feet. Each maker of pointe shoes carries dozens of different models, each varying to accommodate even the slightest differences in foot shape and size, arch height, toe length and shape, and much more.

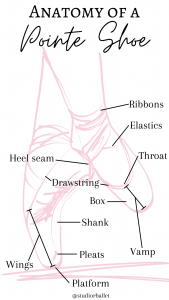

Even with these differences, every pointe shoe has the same basic parts, as shown in the above graphic. Most pointe shoes are made using hardened layers of glue and paper shaped into a toe box and a stiff sole, called a shank, made of leather or cardstock and more glue. The pointe shoe is then covered in canvas and satin and a drawstring is added. Freed of London, a renowned pointe shoe brand, has an incredible video showing some behind-the-scenes footage of pointe shoe production. The whole process is so complicated and intricate that pointe shoes are made by hand, instead of machine-made.

Even with these differences, every pointe shoe has the same basic parts, as shown in the above graphic. Most pointe shoes are made using hardened layers of glue and paper shaped into a toe box and a stiff sole, called a shank, made of leather or cardstock and more glue. The pointe shoe is then covered in canvas and satin and a drawstring is added. Freed of London, a renowned pointe shoe brand, has an incredible video showing some behind-the-scenes footage of pointe shoe production. The whole process is so complicated and intricate that pointe shoes are made by hand, instead of machine-made.

When a dancer buys a new pair of pointe shoes, she still has to measure and sew on ribbons and elastics so that they fit her feet and ankles perfectly. Finally, before they can be worn, pointe shoes have to be broken in. Every dancer has a different method of doing this. Some dancers choose rough methods like slamming the shoes in a door or scratching the platform with a knife or sandpaper to provide traction. Others use more gentle methods, like bending and flexing the box and shank with their hands and repeating relevés in the new shoes until they become more flexible. Once pointe shoes are broken in, they can last anywhere from a few months for beginners to only a performance (or even less than that!) for professionals. Overall, the process of making, sewing, and breaking in pointe shoes is lengthy and complicated. For professionals who go through dozens of pairs every season, it takes up a good portion of their time.

When a dancer buys a new pair of pointe shoes, she still has to measure and sew on ribbons and elastics so that they fit her feet and ankles perfectly. Finally, before they can be worn, pointe shoes have to be broken in. Every dancer has a different method of doing this. Some dancers choose rough methods like slamming the shoes in a door or scratching the platform with a knife or sandpaper to provide traction. Others use more gentle methods, like bending and flexing the box and shank with their hands and repeating relevés in the new shoes until they become more flexible. Once pointe shoes are broken in, they can last anywhere from a few months for beginners to only a performance (or even less than that!) for professionals. Overall, the process of making, sewing, and breaking in pointe shoes is lengthy and complicated. For professionals who go through dozens of pairs every season, it takes up a good portion of their time.

Pointe Shoes at SRB

A big problem in the ballet world is that students who are too young and inexperienced are often put in pointe shoes before they’re ready. Their lack of foot & ankle strength and solid technique very often result in injuries and profoundly poor pointe technique. At Studio R Ballet, we ensure every student is truly ready for pointe work before they are allowed en pointe.  Along with building strong technique, we include many pre-pointe training exercises for our students preparing to go en pointe, to strengthen their muscles and joints as much as possible. Once in pointe shoes, we work first and foremost on slowly building strength and technique instead of teaching flashy tricks. Again, this greatly reduces the risks of injury and shoddy pointe work. We also connect our dancers with professional pointe shoe fitters. An ill-fitted pointe shoe can have disastrous consequences, so it’s extremely important to be fitted by a professional.

Along with building strong technique, we include many pre-pointe training exercises for our students preparing to go en pointe, to strengthen their muscles and joints as much as possible. Once in pointe shoes, we work first and foremost on slowly building strength and technique instead of teaching flashy tricks. Again, this greatly reduces the risks of injury and shoddy pointe work. We also connect our dancers with professional pointe shoe fitters. An ill-fitted pointe shoe can have disastrous consequences, so it’s extremely important to be fitted by a professional.

The history and making of pointe shoes is just as beautiful as the dancing done in them. At Studio R, we take great care to ensure our dancers feel safe, strong, and confident in their pointe shoes.